As Roads Multiply In India, So Does Wildlife Roadkills

By Dr. Oishimaya Sen Nag

Linear infrastructure is both a boon and a bane to rapidly developing India. While it connects people, it often disconnects wildlife if not appropriately planned, which, in the long term, also has detrimental impacts on human populations. Such infrastructure includes roads, railways, power lines, canals, etc., that have a linear nature; hence, their influence is felt along long distances. Habitat loss and fragmentation, wildlife roadkills, restricted wildlife movement and inbreeding, the spread of invasive species, microclimate changes, etc., are some of the adverse effects of linear infrastructure passing through wildlife habitats. This article focuses on India’s growing road network and its impact on wildlife, concentrating primarily on wildlife roadkills and related mitigation measures.

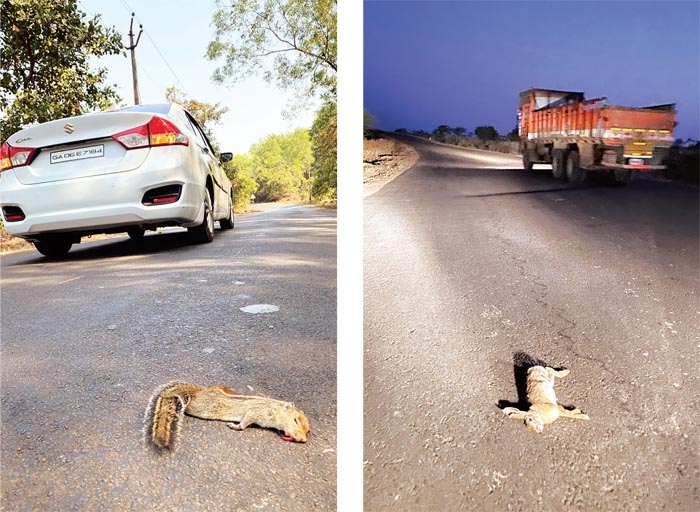

Lethal Roads Yield Shocking Figures

India’s roads, comprising the world’s second-largest road network, cover over 65 lakh km, a massive increase from 54.02 lakh km in 2014. The budget allocated to the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways has also increased from around Rs. 31,130 crore in 2013-14 to a whopping Rs. 2,76,351 crore in 2023-24! By 2037, over two lakh km of national highways are to be built in India, while the number of high-speed roads is to rise by almost ten times! So, what does all this mean for wildlife roadkills?

Here are some hard-hitting facts coming up from research in recent years.

According to a 2020 study published in Science Advances on the risk posed to tigers by road development in Asia, increased vehicular traffic in India is likely increasing the mortality of tigers and their prey species due to collisions with vehicles on the country’s roads.

From 2015 to 2017, India lost at least ten tigers as roadkills, which is believed to be an underestimate, with many cases possibly going unreported. Additionally, tiger extinction risk also increased with genetic isolation due to more traffic on roads, separating tiger populations from each other.

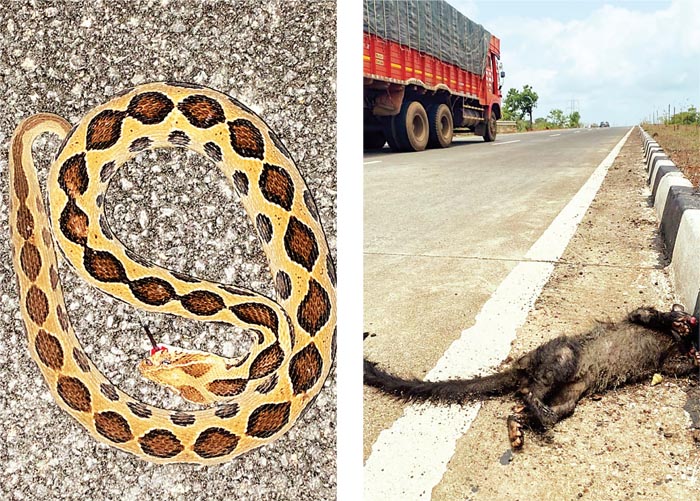

In neighbouring Rajasthan, a 2020 study found roads adjacent to the Desert National Park were deadly to the park’s wildlife, with 289 roadkills detected from January 2016 to December 2016. Reptilians were the most affected group, making conservationists fear about the future of the park’s reptilians. The study was reported in the Asian Journal of Conservation Biology.

The number of roadkills increased over the years. The study was published in the Herpetological Conservation and Biology journal.

With an expanding road network in the Himalayas, roadkills are also rising in the region. A recent study in Jammu and Kashmir published in the Journal of Threatened Taxa found 49 wild animal carcasses on or around a 120 km stretch of NH244 over a period of 33 months. Mammals were most affected, with golden jackals, rhesus macaques, and red foxes suffering the highest number of fatalities in this animal group. Two carcasses of the leopard and two of the

Himalayan vulture, both highly threatened species, were also discovered. Researchers found nocturnal mammals most vulnerable to vehicular collisions in the study area. Another study published in 2022 in the International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences found 64 roadkills in six months (March to August 2019) across a 45 km stretch of NH1 in Jammu and Kashmir. Mammals comprised the majority (37.5%) of the kills.

These sporadic roadkill reports produced by small research groups are just the tip of the iceberg. The total damage is expected to be many times worse. Roads across the country are killing thousands of species of fauna. Not all fauna groups are affected equally. Herpetofauna, especially reptiles, are more prone to being crushed down by vehicles due to their slow movement, poor response to approaching vehicles, small size and lack of awareness

among drivers about their road-crossing activities.

However, other vertebrate groups are also increasingly becoming more susceptible to roadkill. Even birds are not spared. Ground-dwelling birds, low-flying birds, or those that tend to forage or scavenge for food on the road are more susceptible to vehicle strikes. For example, a study published in the Journal of Threatened Taxa in 2020 reported avian vehicular roadkills in Tiruchirappalli District of Tamil Nadu. From January 2016 to December 2016, periodic road surveys across a 41 km stretch of state highway found 64 bird roadkills of 12 species. The most affected species were the Southern coucal, common myna, house crow, and spotted owlet.

While large mammal roadkills like those of tigers or leopards receive some attention from the media and the public, most other wildlife roadkills go unnoticed. The invertebrate roadkills are, of course, the most ignored, with millions of butterflies, bees, and other insects and arachnids getting crushed under deadly wheels on the road or colliding with vehicles as they fly across roads. These go unreported and undocumented even by research and conservation communities.

Prevention and Cure

According to experts, the best method of protecting wildlife from roadkill is to prevent the construction of roads through wildlife-rich areas. However, in cases where such construction is completely unavoidable, a plethora of measures can be implemented to reduce the impact of the linear infrastructure.

Warning signs for drivers in “hotspot” areas reminding them to drive slow can potentially prevent collisions. Road design can incorporate various elements to automatically reduce vehicular speed, while traffic calming treatments can also be implemented. Of course, wildlife passage structures like overpasses and underpasses complemented with fencing can also significantly reduce roadkill incidents. Evening or dawn/dusk or seasonal closure of roads passing through wildlife habitats can also be a potential solution to reduce the frequency of roadkills during periods when wildlife is most active.

Related Posts

Strangulation by cementing is the silent killer of trees in urban environments

Strangulation by cementing is the silentkiller of trees in urban environments By Sundararaj R, Swetha…

Guardians of Grey Headed

Guardians of Grey Headed Observations by CA. Shomi Gupta & Yogesh More The Grey Headed…

Tree Translocation of 1000 trees in Balliguda Forest Division

Tree Translocation of 1000 trees in Balliguda Forest Division By Vishwanath Neelannavar, IFS As per…

Participation of women in Natural Resource Management

Participation of women in Natural Resource Management By Anubha Srivastav and Anita Tomar Natural Resource…