By : Dr. H.S. Pabla

Back from the Brink

Wild life and wild spaces have declined on earth due to growth in human population and man’s capacity to modify the world. This decline has been much faster in the last 200 years when man started extensive use of fossil fuels to power the transportation and industrial machines. Growth in human population during this period has also been the highest in history mainly due to our mastery over mass killers like, plague, cholera, small pox etc. Perhaps, also, due to the progressive decrease in the frequency of wars. Many species of animals have since been wiped out either due to overhunting or due to the destruction of their habitat, often both.

The decline of wildlife was much faster in industrialised countries, despite their relatively smaller populations. Thus species like the grizzly and brown bears, wolf, bison etc. were wiped out over most of Europe and America either because they were seen as a danger or because they were outstanding hunting trophies. Species like the, badger, beaver, fox, mink etc. were decimated for their fur which was used in high fashion in Europe since the 16th century.

Many of these species experienced widespread extirpation and had to be reintroduced back into the wild. The creation of protected areas (PAs) was not enough to bring them back. Efforts to reintroduce the grizzly, wolf, bison etc. both in Europe and America began in the late twentieth century. They have already spread into many of their former habitats and are now considered safe from extinction in the near future.

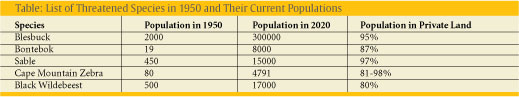

Revival of wildlife in Africa started around 1950 when a large number of cattle farms were converted into private game reserves for the purpose of hunting and tourism. This movement not only converted vast tracts of farmland into wildlife habitat, it also encouraged wildlife ranchers to stock them with species popular for, tourism, sport hunting and meat production. Because of the economic value of wild animals, the area under private game reserves in South Africa(Approximately 24 million Ha) is now over three times the area of public lands under protected areas, holding approximately 18 million wild animals, mostly purchased from national parks and from each other.

The economics of wildlife also spawned a wildlife capture and translocation industry which helped in the development of sophisticated technology and equipment for wildlife management in Africa. Wildlife ranching for hunting and tourism is the backbone of the economies of most African nations now. At the same time many endangered species are flourishing in the private game reserves. The table below gives the current and past populations of some of the endangered species of wild animals in South Africa.

While the decline of wildlife in Africa, Europe and America was more due to overhunting than habitat loss, in India the decline has been due to habitat loss and degradation in equal measure. The country has about 20% of its geographic area under forests, but only about 5%(Protected Areas) has any significant wildlife populations. While the countries mentioned above decided to actively reverse the local extinctions of wildlife for economic or ecological reasons, India continues to watch the depletion of its wildlife over most landscapes helplessly. The only thing we did to conserve wildlife was to declare some forests as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries i.e. PAs. Although that helped, PAs themselves continued to lose species after species. The Minister for Environment and Forests informed the Parliament in 2009 that 16 of the tiger reserves had no or few tigers. Sariska and Panna tiger reserves made headlines for losing all their tigers, presumably to poaching, in 2005 and 2009 respectively, but nobody had noticed the demise of other species even from PAs and other forests. For example, nobody mourned the loss of gaur from Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve in the 1990s and blackbuck from Kanha around the same time. The hard ground barasingha, a deer which once occupied the whole of Central India, was now confined to Kanha Tiger Reserve. These examples are from Madhya Pradesh alone. It must be the same in other states. Although the populations of tigers, elephants etc. seem to have made impressive recoveries in the last decade or so, perhaps as a result of improved protection, the march of local extinctions continues inexorably as pressures of poaching and habitat loss continue to mount due to increasing human population and prosperity.

While the world had learnt to repopulate depleted habitats through translocation long ago, India had never tried a hand at this skill. The only successful introduction of a major animal in a new habitat, the one-horned rhino in Dudhwa National Park, was done by foreign experts, way back in 1980s. We did not try to build this capacity simply because it is a complex and expensive business without any potential economic returns. This is because India had opted for a conservation model where hunting was banned and tourism was only reluctantly allowed. Thus, there was no way how the expenses on the mass translocation of any animal could be recovered. For a poor country like India, economics matters more than ecology, like it or not. Thus, our wildlife continues to deplete, from forest after forest, without any hope of redemption. Even where translocation of animals was necessary, we could not do it because we did not know how to capture and transport wild animals. We did not know it because we had never tried to do it. We did not do it because wild animals are not important to the livelihoods of Indians. In fact, the lesser the better, as more animals means more losses, fear and discomfort.

However, in the middle of this vicious cycle, Madhya Pradesh forest department decided to stem the march of local extinctions some time ago. Although the longawaited introduction of the Asiatic lion into the forests of the state is still hanging fire due to the interstate wranglings, several locally extinct species have returned to their former domains in the last decade. Tigers are roaring in Panna again, gaur is mooing and lowing in Bandhavgarh and blackbuck is sprinting in Kanha meadows again. Most significantly, the threat of imminent extinction of the barasingha (swamp deer) has now been averted as another population, though small at present, has been created in Satpura Tiger Reserve, nearly 150 years after the species was last reported in that tract. All this happened through translocation of founder animals from other parks of the state. Thousands of deer are being moved between parks of the state every year now. No animal should go extinct in the state now, as the forest department has the capacity to avert or reverse local extinctions through translocations.

How did it all happen?

It all started quite fortuitously around 2006. While the forest department was wondering why species after species were being lost from the state’s national parks, despite the best possible protection, a South African company called & Beyond (And Beyond), which owned private game reserves in Africa, decided to build wildlife lodges in the state, in partnership with the Taj Hotels of India. The joint venture was named as Taj Safaris. When the officials of the company came for a courtesy call to the office of the Chief Wild Life Warden (CWLW), they expressed their desire to contribute to the strengthening of wildlife conservation in India.

During the conversation, it came out that & Beyond had long experience in the translocation of large mammals. So, the officials asked Taj Safaris to help build the capacity of the forest department in this field. The visitors promptly agreed and offered all help. It was decided that a project to reintroduce gaur in Bandhavgarh National Park, through translocation from Kanha, would be developed and implemented jointly for this purpose. Intensive preparations for the venture were done over the next five years. Veterinarians and other officials were trained in capture and handling of large animals, both in India and South Africa. Vehicles and other equipment were customized as per South African standards. A sophisticated portable enclosure, called boma in South Africa, was prepared in Kanha along with a 100 hectare boma to receive the animals in Bandhavgarh. Every bend and bump in the road from Kanha to Bandhavgarh was surveyed and mapped in order to ensure the transportation of animals without any trauma. Narcotic drugs to immobilize and tranquilise the animals were imported from South Africa. Finally, despite several setbacks, 19 gaurs moved into Bandhavgarh in the winter of 2010-11 and another 31 in the next winter. Now they are over 150 and seem to have become completely naturalized in their new home, with regular births and deaths.

Gaurs in Bandhavgarh

The success of this project encouraged the forest department to restore the lost biodiversity of other parks of the state. 50 blackbucks were captured from the croplands of an adjoining district and moved into Kanha Tiger Reserve with the help of Chenchu tribals from Telengana, in November 2011. Preparations for translocating 50 barasinghas to the Satpura Tiger Reserve began in 2011 and the animals finally travelled 400 km to their new home in 2015. Since then thousands of spotted deer have travelled from one park to another as the active management bug has bitten the foresters of Madhya Pradesh.

Tigers Breeding in Panna Again

The extinction of tigers in Panna Tiger Reserve created an opportunity to learn the art of restoring carnivore populations.

While Sariska Tiger Reserve, which had lost its tigers five years earlier, was struggling with reintroduction, Panna created history by successfully recreating a new tiger population through translocation, starting 2009. This operation also included the rewilding of tigers raised in captivity, thus opening the door for the creation of wild tiger populations from zoo born animals, if ever the need arises in future. Panna is now a flourishing tiger reserve. It is not only full of tigers to its capacity, but it is also contributing to the strengthening of tiger populations in other parks like Sanjay Tiger Reserve and Satpura Tiger Reserves. Tigers from Panna are also migrating into Uttar Pradesh now. A new tiger population, founded by tigers translocated from Bandhavgarh, is building up in the Noradehi wildlife sanctuary of the state, thanks to the experience gained from Panna.

Although it is not a smooth road, a new era of active management of wildlife seems to have begun in India. Many other states and countries are trying to learn from the experience of Madhya Pradesh. Although the attempt to translocate tigers from Kanha to Satkosia Tiger Reserve of Odisha seems to have failed due to some faulty planning, we can now hope that wild animals need not become extinct, as their populations can be reinforced or recreated, if needed.

However, the fundamental question is why we should do it. Conservation of wild animals is an expensive exercise and even rich countries struggle to fund it adequately. Other countries invest in conservation of wildlife because wildlife based jobs are a major driver of their economies and social agenda. In India, wild animals only cause destruction and mayhem. Although we can gloat over these preliminary successes, such expensive ventures are not sustainable in the long run unless we find a way of making wildlife pay for its upkeep. We may have leant how to bring wild animals back from the brink, but unless we figure out why we need to do it, this new capacity will remain an aimless acquisition.