The Rising Tiger Deaths in Bandhav garh-Causes and Possible Solutions

By Dr. Suhas Kumar, IFS

27 tigers were killed over the last 2 years and 2 months till the first week of March 2024. Most cases are reported as territorial fights, while my scrutiny of the cases reveals at least 6 tiger deaths that demanded a thorough investigation were not investigated properly to reach a logical conclusion. This means investigations are not being carried out as per the Standard Operating Procedures (SoP) prescribed by the NTCA for investigating tiger and leopard deaths. A case of tiger death discovered by staff on 3 March 2024 is prima facie a case of poisoning as the unusual bloating of the carcass indicates. As we will find in this note, the data reveal that Tiger attacks on cattle and humans have increased manifold. Why is this happening?

Before I delve into the conclusions drawn from the tiger death data, I would like to apprise the readers of the management history of Bandhavgarh.

Bandhavgarh National Park was noti fied in 1968 under the Madhya Pradesh National Park Act 1955, covering an area of 105 sq. km. of Tala Reserved Forest Block. There were two small hamlets within this area. Both were relocated out in 1978-79. The level of protection given to this area as a National Park yielded exceedingly good results with the significant improvement of the habitat that soon resulted in the proliferation of wildlife. Looking at the increasing wildlife population, the State Government in 1982 declared its intention to enlarge the Park area by adding 343.84 sq. km. area. Subsequently, in 1983, the Govt. of Mad hya Pradesh notified 245.842 sq. km. of Umaria Forest Division as Panpatha Wildlife Sanctuary, which forms the northern boundary of the Khitauli Range of the extended part of the National Park.

However, the Sanctuary came under the unified management of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve after 12 years in September 1995. The other ranges added to the national park in 1982 came with 15 villages inside them. Besides the anthropogenic pressures on the corearea from outside its boundary are enormous. Around 1 lakh humans and an equal number of cattle live around it. Out of 96 villages of the buffer 66 are within 3 km of the core boundary, and many among those are just on the coreperiphery.

In 2007, the state government notified an area of 716.905 sq. km as the core zone (including the Panpatha sanctuary), and 820.035 sq. km was notified later as its buffer zone. Unfortunately, for a very long time, the managers’ focus, who were posted in Bandhavgarh from time to time, was tourism, therefore, only the Tala range received managerial inputs while the other ranges remained neglected till 2005. From 2005 onwards some serious managers tried to improvethe habitats infested by Lantana and other weeds in the ranges that were added to the national park in 1982. But the other aspects of management like control of grazing, poaching and fire control remained a lingering issue and the peripheral villages and cattle continued to exert huge biotic pressure on the national park. A concerted village relocation plan was implemented in Bandhavgarh after 2012 and the vacated village sites wereconverted into verdant grasslands. This intervention changed the entire scenario in favour of wildlife.

Recent Changes in Bandhavgarh

In Bandhavgarh, the decimating factors are already in operation. I think the grasslands in some areas have deteriorated due to heavy grazing by wild herbivores taking a toll on the ungulate

population now. This may be confirmed by assessing Phase 4 monitoring data. In the core area water is not a limiting factor but in the buffer zone with heavy human presence water is not easily accessible to wild animals.

I also believe that cub killing, and frequent territorial fights, which were rare in Bandhavgarh 10 years ago have increased as strife, disease and disaster are Nature’s way of maintaining a bal ance in the ecosystems. Besides Nature’s population-controlling mechanisms, the

human-orchestrated decimating factors are also active. After examining data on tiger deaths from Bandhavgarh over the last five years I am of the firm opinion that retaliatory killings and poaching both are in operation in Bandhavgarh. On my request, the forest department has ordered a thorough re-examination of 27 cases of tiger deaths by the State Tiger Strike Force to determine the causes of tiger deaths and devise an appropriate strategy to curb poaching. There is ample provocation to villagers for the retaliatory killing of tigers. Even when the tiger number was not as high as now (around 63 tigers in 2014) frequent human-tiger conflicts were common.

One of the most obvious reasons is the presence of several villages just outside the core boundary and the illegal ingress of locals within the core area. The majority of the incidents were observed within the protected area and around the park boundary. A total of 17 cases of tiger attack events on humans were recorded from April 2011 to April 2015, out of which 53 % (n=9) of the attacks resulted in the death of the victim. Surprisingly the average human death per year has gone down to less than 4 now but the average number of injury cases due to tiger attacks has gone up to around 88/year (2018-19 to 2021-22). The data indicate that most attacks might have been perpetrated by young and inexperienced tigers that encounter human beings frequently while making forays into the human-dominated buffer zone to prey on cattle.

Possible strategy to tackle the current situation

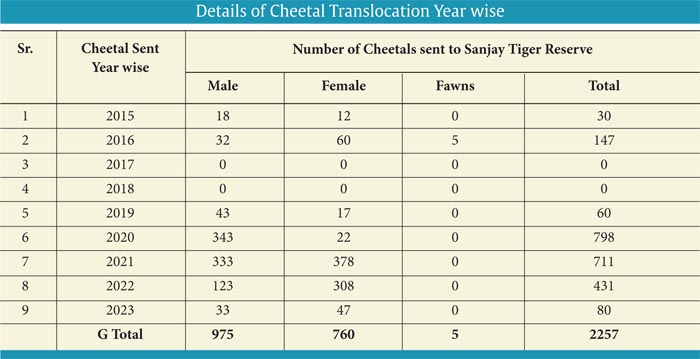

- Stop Translocating Chital from Bandhavgarh The capture and removal of chital from Bandhavgarh must stop immedi ately and restoration of grasslands should be taken up urgently.

- Expedite relocation of villages The relocation of the remaining 8 villages and grassland development must be expedited. The CWLW should prepare areas like the proposed Omkareshwar National Park to accommodate tigers from areas where conflict has escalated or where tigers are roaming in very high risk areas.

- Restore Corridors Highly disturbed Corridors to other tiger reserves (Kanha, Achankmar,Panna, Nauradehi, Guru Ghasidas, and Sanjay Dubri have made the situation worse. To sustain the population for the future and avoid inbreeding, maintenance of connectivity through corridors in the landscape is essential. The state govern. ment, therefore, must act fast to restore at least some of the corridors. Restoring the corridor will also help ease the current level of conflict.

- Regular review of the cases of human deaths and tiger deaths by the Field directors and CWLW must become a norm.

- Hands-on training in crime scene investigation, collection of evidence, collection and preservation of the samples from the carcass, and preparation of necessary documents must be mandatory.

- A State and National Level Tiger Relocation Programme needs to be initiated by NTCA As many notified tiger reserves in the country have no tigers or are inhabited by an unviable population of tigers there is ample scope for intra and inter-state relocation of tigers. Besides, several states still have enough usable tiger habitats (In M.P. there are some extensive undisturbed habitats like the proposed Omkareshwar National Park (645 sq. Km), Lagur in Balaghat, and several other forest areas that have been recently identified and mapped using GIS). These areas need to be mapped and secured by providing them with adequate legal status as a PA or at least a management umbrella such as making them a wildlife division, posting adequate staff, ensuring their training in wildlife management and protection, assessing the prey situation, preparing a prey augmentation plan before bringing in tigers. Translocating adequate prey species from tiger reserves and farmlands facing severe crop depredation may be explored. Any translocation of the prey spp. from PAs must be done after a thorough study to assess the removable availability of herbivores in other areas.

Related Posts

Strangulation by cementing is the silent killer of trees in urban environments

Strangulation by cementing is the silentkiller of trees in urban environments By Sundararaj R, Swetha…

Guardians of Grey Headed

Guardians of Grey Headed Observations by CA. Shomi Gupta & Yogesh More The Grey Headed…

Tree Translocation of 1000 trees in Balliguda Forest Division

Tree Translocation of 1000 trees in Balliguda Forest Division By Vishwanath Neelannavar, IFS As per…

Participation of women in Natural Resource Management

Participation of women in Natural Resource Management By Anubha Srivastav and Anita Tomar Natural Resource…