A trench dug to stop elephants from crossing into farmlands around Kibale National Park, Uganda

By: Taddeo Rusoke

Agriculture and proximity to protected areas – What’s the future for people and wildlife?

I delve into yet another important discussion that could shape human-wildlife conflicts (HWC) mitigation in Uganda and across Africa. The interest of this discussion is to contribute mitigation

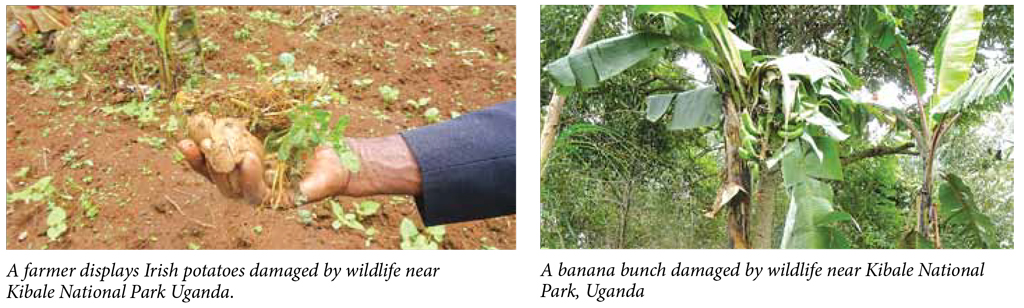

of HWC emanating from crop damage by wildlife as I figure out to understand loss of crops to wildlife around Kibale National Park in western Uganda. Except for farming practices, knowledge of crops to grow, interventions designed to stop animals from crossing into crop farms, level of education of farmers, farmer-led crop protection methods, protected areainitiated crop protection interventions and the nature of wild animals found in a given national park, proximity to the protected area boundary plays a crucial role in managing loss of livelihoods among protected area communities.

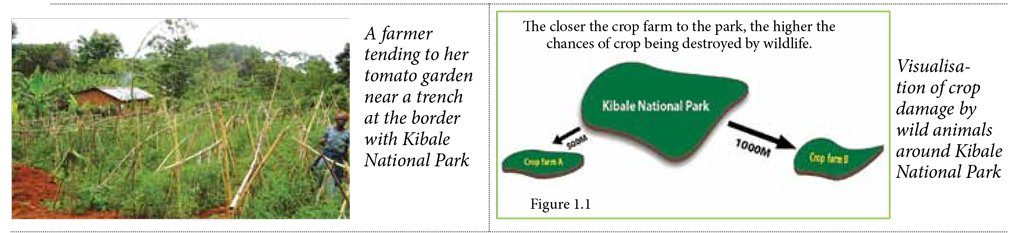

Crop farms in proximity to the Kibale National Park boundary are damaged most as opposed to those farms located farther from the park boundary. Farms within 500 metres from the boundary of the park are heavily damaged by wild animals straying from the national park compared to farms located in 1000 metres from the boundary. This implies that farmers near the park boundary act as a buffer for those farming distantly from the park. All interventions for crop damage management must target farmers in proximity to the national park boundary. Which are these crop protection interventions aimed at stopping human wildlife conflicts?.

These are interventions designed to stop animals from crossing into gardens and damaging farmers crops. Some of these include digging of elephant trenches, setting up of beehive fences, establishing elephant deterrent boards, encouraging farmers to plant buffer crops, park authorities scare-shooting strayed wildlife back to the national parks especially elephants and buffaloes,

planting Mauritius thorns, and crop farmers setting up scarecrows in their gardens especially to scare away birds, guarding of crop farms with help from dogs, chasing crop damaging wildlife

from gardens by throwing stones, lighting fires at night to keep watch of wildlife and guard crops among others.

Around Kibale National Park by the month of April 2021 an elephant trench network of about 82.5 kms had been dug in parishes where wildlife is reported to damage crops most. Between 1000-1300 beehives have been distributed among farmers in parishes experiencing high intensity of crop damage by wildlife to set up beehives. Rangers are also always alert to repulse back strayed animals back to the park. Despite of such efforts, there is need for more funding to maintain the already existing trench network, dig more trenches and supply more beehives. It has been discovered that where trenches are not well maintained, elephants can push back the soil and cross into the community and damage gardens.

As a frequent travel around Uganda and Africa in general, most times I travel to national parks I take keen interest in observing what is happening around these protected areas in terms of sources of livelihoods. I quite often interact with communities around national parks during my research engagements. These interactions aim at visualising scenarios and consequently writing conservation stories that could shape future conservation planning in Uganda and Africa at large. In Figure 1.1, I visualise how distance of crop gardens from the park could influence damage by wild animals.

Human-wildlife conflicts especially those arising from crop damage should not be looked at as mere conservation concerns as farmers in Uganda and across Africa reap tears. Moving towards co-existence is crucial for people and wild animals. It should be noted that with constrained budgets for protected area management, most times farmers are not adequately compensated or go uncompensated for crops lost to wild animals, and this can result in retaliatory killing of wildlife, resentment of wild animals, increased poaching and lack of support for conservation programmes

across Uganda and Africa at large.

Gross et al., (2021) observes that a future for people and wildlife is premised on maintaining connectivity for wildlife through human-dominated habitats, being innovative through technological transformations, forging more collaborations and partnerships to foster exchange of best practices, increasing funding for crop protection interventions, and conducting more research on

inter and transdisciplinary approaches to the management of crop damage by wildlife keeping tabs on changing trends in climate, urbanisation, and changes in agricultural land uses across protected areas.